What is the length of the Mississippi River? Sounds like a fairly straight forward question but a concept known as anchoring (or magnitude priming) makes people respond to that question in unexpected ways.

Anchoring is psychology theory that suggests when people see a number, they are biased toward that initial number. What does that mean? Let’s try an example. Consider the following question:

A. “Is the population of Chicago more or less than 5 million? What is the population of Chicago?”

Now, think of your answer. What if I would have asked Question B (below) instead?

B. “Is the population of Chicago more or less than 500 thousand? What is the population of Chicago?”

A consumer psychology theory known as anchoring suggests you are biased toward the number I provided. Take a closer look. In Question A, I asked if Chicago was more or less than 5 million and in Question B, I asked if the population of Chicago was more or less than 500 thousand. How does that number affect you? Studies show that the people who are asked the question with 5 million respond with a higher number than the people who are asked the question with 500 thousand.

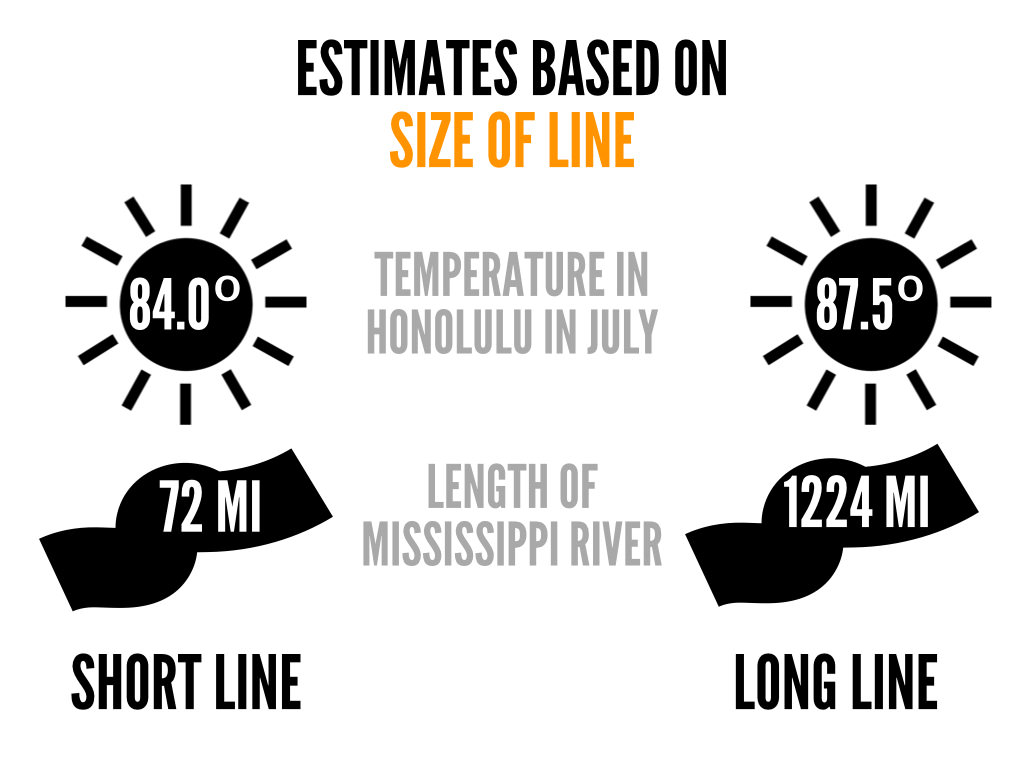

Other academic research suggests this same effect can occur with purchase quantity limits or, in the case of this post, when big or small thoughts are cued by a physical action. How big of an action? Simply drawing a big or small line had an effect. Researchers had one group of people draw a short line while another group of people drew a long line. Both groups were then asked (among other questions) to estimate the length of the Mississippi River.

The group that drew a long line estimated the length of the Mississippi River was 1,224 miles while the group that drew a short line guessed 72 miles. The actual answer is 2,320 miles. I’ll skip the discussion of the geographic knowledge of students in the United States (72 miles?!) but suffice to say, answers may be heavily swayed based on a small action. The study was replicated to show a similar effect (after drawing a long versus short lines) on estimates of the temperature in Hawaii in July. The group that drew a small line was “anchored” or “primed” to think small while the group that drew a long line was “anchored” or “primed” to think big. A simple physical action that drastically affected behavior.

How might the theory of anchoring affect your business? Let me know in the comments. We can always brainstorm new studies!

Sources:

Jacowitz, K. E., & Kahneman, D. (1995). Measures of Anchoring in Estimation Tasks. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(11), 1161–1166. doi:10.1177/01461672952111004

Oppenheimer, D. M., LeBoeuf, R. & Brewer, N. T. (2008). Anchors aweigh: a demonstration of cross-modality anchoring and magnitude priming. Cognition, 106(1), 13–26. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2006.12.008

Comments

One response to “Psychology of Anchoring and Influence On Behaviors”

[…] have talked about anchoring a couple times on my blog so I’ll save a long explanation. The general idea is you are priming someone […]